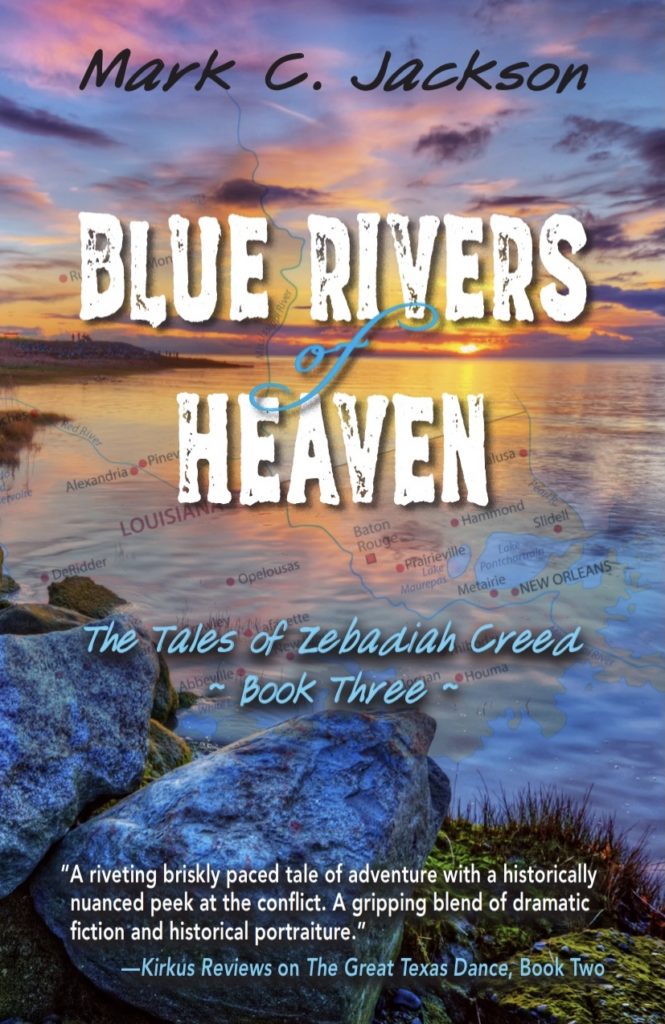

Blue Rivers of Heaven, the third novel of the series The Tales of Zebadiah Creed is on sale now!

What Are The Best Online Casinos In Australia To Make Money From Playing Pokies With A Deposit If online gambling is legal in your state, you can sign up to a site and claim your risk free bet promotion. What Are The Best Free Online Pokies Games In Australia With No Tax Once you pay the corresponding amount, you will be given a ticket. What Are The Best Online Pokies To Play For Free With No Download In Australia

Blue Rivers of Heaven, the third novel of the series The Tales of Zebadiah Creed is on sale now!

Dear friends,

You are cordially invited to our book signing party on Saturday, January 14th, from 6:30 to 8:30PM to celebrate the world-wide release of our new books Save the Last Bullet: Memoir of a Boy Soldier in Hitler’s Army and Blue Rivers of Heaven.

There will be a little bit of reading, a little bit of Q&A and a lot of celebrating!

We’ll have books for sale with cash, PayPal, or Venmo.Bring a friend and join us for a couple of hours of fun.

We look forward to seeing you there!

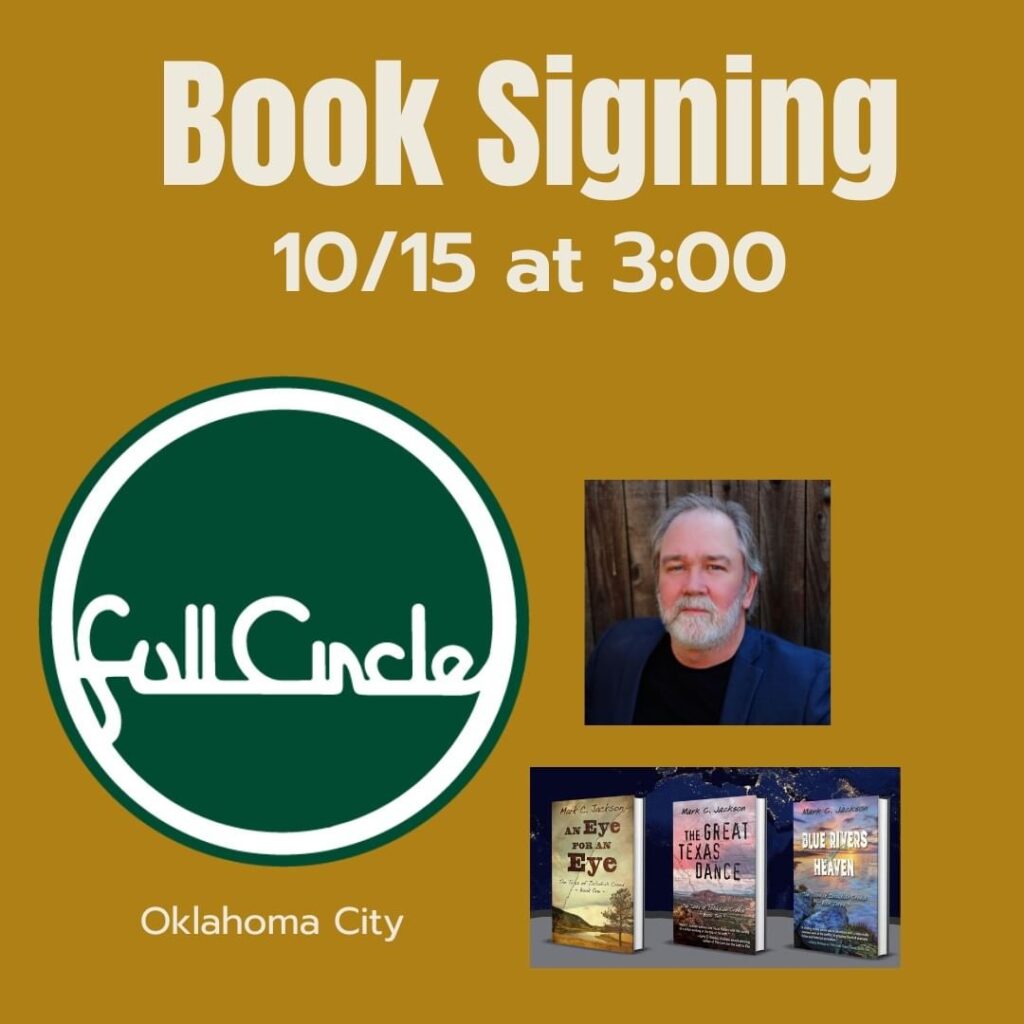

Join Mark at Full Circle Bookstore for his second book signing in Oklahoma City.

After 12 years, I finally made it back to the cover of The San Diego Troubadour. Check it out: https://sandiegotroubadour.com/mark-c-jackson-has-a-story-or-3-to-tell/

(Featuring Chris Enss)

Written by Mark along with David R. Morgan, Pamela Haan, and Chris Enss, who sings the song.

For Liquid Flag Productions.

Soon to be released to your favorite streaming service.

Continued . . .

By the time I met Chet Cunningham in 2012 I had written the 600 word short story The Hanging, the 5000 word story tentatively called Zebadiah Goes to New Orleans and was 23,000 words into Zebadiah Goes to Texas. Chet loved the Hanging, hated New Orleans and I don’t think he ever read Texas. Based on the Hanging, he invited me to join the oldest writers group in the city that he founded in the 60s called The San Diego Professional Writers Group. Talk about being intimidated! These folks were real writers. For my first meeting, he told me to just show up and listen. Which I did. Two weeks later, at my second meeting, I read The Hanging for critique. Sitting there listening to these writers make the rounds, then read their latest chapters from their latest book, well . . . like I said, they were real writers! I nervously read my piece. Each person had something different to say as I feverously wrote down their comments. I still have the copies archived with Peggy, Tim, Jim, and Chet’s handwritten comments written on them. They said good work and invited me back in two weeks. I left thinking I may actually have something here.

Chet Cunningham wrote up until two weeks before he died in 2017. He was 88 years old. During his lifetime, he wrote and published at least 375 books. He wrote in all genres, fiction and non-fiction alike. He wrote a self-help medical book about his wife’s ailment. He wrote several books on WW2. He’d write the military fiction series Seal Team Six, then turn around and write The Executioner series under a pseudonym. The next week, he’d be writing the western series Spur. His daughter Christine Ashworth, a writer herself, told the story of him being asked by a publisher to write a book for a series under another author’s name. He placed tape across the door of his office and told his family to leave him be. He wrote the book on deadline, in five days.

For over 50 years, he never stopped making his living as a writer. Along the way, he was always generous with his time, sharing his deep experience and love for the written word to those of us who were absolutely willing to go to our desks every day and write. In my case, it was every evening for I worked a full time job.

Chet became my mentor and I became his friend.

Sometime after I joined the group, I wandered into our local Barnes & Noble. I thought, maybe there might be a magazine about writing. I found two, The Writers Magazine and Writers Digest. For the next six years, I made a pilgrimage to that bookstore to buy those magazines. I read them from cover to cover. This is how I learned the craft of writing.

To be Continued . . .

Continued . . .

I don’t know why I decided to place Zeb in New Orleans in October 1835. The short story The Hanging took place somewhere along the Cimarron Trail in the winter of 1846. I guess I wanted to find out what was going on in his life 11 years before. I figured he would have been about 24 years old.

Once I started writing the second story, I realized I didn’t know Zeb last name. At first, he wasn’t even Zeb, or Zebadiah, he was Jeb. Then I thought, hell, there were many Jebs out there in books, Though, not many Zebs, that I could find.

So, I told my friend Tim Chandler a little about what I was doing. For years Tim had tried to get me to go with him to one of a couple of local Rendezvous re-enactments held locally in our mountains. I was familiar with them but had never attended one.

In the early 19th Century, a rendezvous was an annual event held somewhere in the Western United States where all the fur trappers (mountain men) in the area gathered to trade and sell their goods. The local Indian tribes were invited as were the companies buying the beaver furs. From there, they were shipped to the Mississippi River down to New Orleans and on to England, where they were made into top hats. The American Fur Company was the most prosperous, making it’s owner, John Jacob Astor the first millionaire of our nation. The rendezvous’ of today are re-enactments where the participants spend their entire time wearing authentic dress, camping, and celebrating the lives of the mountain men. Anyway, one day, I asked Tim what he thought Zebadiah’s last name was. He came back a few minutes later and said, “Creed, his last name is Creed.” I thought, hmm, Zebadiah Creed, that’s about as perfect a name as you can get.

I couple of years later, I did indeed attend a rendezvous with Tim near Big Bear, California.

Back to New Orleans, 1835.

Why was Zeb there, I asked myself. As I started to write a first sentence, a first paragraph, the first chapter, I began to understand. And I was amazed.

For lack of no other title at the time, I called it “Zebadiah Goes to New Orleans”.

“You get caught up in them mountains it’s a long time ‘tween summers.”

Blue smoke curled lazily up from an ember burning in the pipe. She breathed in, then asked, “Why do you go there Monsieur Zebadiah?”

I did not answer.

Her name was Sophie le Roux, a French woman with a bit of Indian in her. But for lines of age and opium stained lips, she was still a most beautiful woman. Her eyes shined black diamonds. I was fortunate to be in her favor for she was also the richest madam in New Orleans.

She brushed back a whisp of black hair and closed her eyes. “So my Mountain Man, what brings you back to New Orleans and to me?”

Wind and rain blew against a small, cracked window beside a plain four post bed. Lit by only an oil lamp, her room was spartan compared to other women of her sort. A porcelain water bowl, pitcher and matching chamber pot lay pushed against the wall next to the door. On a low square table sat a dusty bottle of cognac with two crystal glasses and a gold and copper water pipe. Between the chairs we sat in, burning embers glowed in a cast iron kettle. Of course, this was her sleeping room, not her entertaining room. No one knew we were there.

“You are familiar with a certain Englishman I seek . . .”

She opened her eyes. “I am familiar with many Englishmen. A few I am fond of, most I am not. Why do you seek this man?”

I picked up my glass and said, “I’ll just say he owes me.”

She took a long draw from the pipe. “We do not leave this life owing no one. A man will only fight over a woman or an insult, which is it for you Monsieur Zebadiah?”

I stood, walked to the window and stared down at a dark, muddy street and the black swamp beyond. For an instant I saw a flicker of light, perhaps a boat lantern, quickly hidden or extinguished. I turned back to her and said, “An insult, thievery and spilt blood.”

“What is this Englishman’s name?”

“Benjamin Brody.”

“Ah, Monsieur Brody . . .” She whispered.

Her black eyes shone through blue smoke. “You have bathed and are now wearing a clean shirt, new britches and boots. My ladies have taken good care of you, yes? You have eaten and drank well with intimate conversation? And your wound, it is almost healed?”

“My wound?”

“Darling, my girls tell their madam everything.”

She stood and stretched. Reaching up, it seemed her long, thin fingers touched the ceiling. She closed her eyes again and begun to dance. The rain had slowed to a drizzle and but for the whoosh of her petticoat, the room was silent. I sat down on the bed and finished my drink. I could just hear her breathing, then humming; a waltz to go with her dance, a ghost melody she seemed to only half recollect. With her eyes still closed, she unhooked the top of her dress.

“You will stay the night with me, no Monsieur Zebadiah? Tomorrow we shall discuss how to accommodate you further with this Englishman Brody. One more question then no more, I ask again why you go to the mountain when everything is here in this room?”

She finished unhooking her dress and slipped out of the petticoat, then undergarments. Glistening by oil lamp, she stood naked before me.

I could not think to answer her properly.

To be Continued . . .

The first night, we built our shelter around three trees, using buffalo hides. An unexpected blue norther swept across the prairie, cutting through the flimsy, wet clothes the eastern folk wore. The fire kept blowing out and I was obliged to keep it lit. It being early fall, we were not supposed to be caught by the weather. A week’s travel was what I was responsible for and that was all, get ‘em there and I’d be back home. Earlier in the day, crossing the Cimarron, a flood upriver caused by a thunder burst swept their two wagons away, leaving them only their feet for means of traveling. They praised God no one died.

They spent the next day walking. I rode a horse.

The second night, we sheltered in an abandoned cabin. The fire stayed lit. At dusk, I left to find food. As I returned, a woman stood before me. I had never seen one’s eyes so filled with fright.

“What happened?” I asked.

“She was unfaithful to her husband, he found out,” a man said.

Now, how could that be way out here, I thought.

Next, I saw her hanging from a tree.

I had this dream when I was about twenty years old. When it came time to find the last of five prompts for a writing class I took on a whim, I remembered, as if it were the night before, the woman hung from a tree. I wrote a 600 word short story called The Hanging. One student said that it was flawless. The professor who taught the class held high praise for my “writing”.

I was 53 years old.

“Hell,” I thought, “maybe I can write more.”

So, I had the audacity to keep going, for I had found Zebadiah Creed.

The Hanging

Cimarron Trail, mid-winter 1846

William hung her at sunset, or shortly before; hung her from an old, barren oak not far from camp. He must have hit her in the head when no one was looking and dragged her off. When I walked up, most of my party was there watching her sway in the wind and he was sitting staring at the ground.

“Why’d you kill her?” I hollered, the crowd turning to me.

I dropped three rabbits to the ground but held my rifle. “Why’d you kill her, William?” The crowd backed away a little. It was almost dark, getting cold, and nobody had eaten since the morning.

Ten days before, we left Dodge City to cross through the Cimarron. So far, I lost them pretty much everything they owned, including three of their kin and the brother of the man who just hung his wife.

“She was unfaithful to me Zeb. Her and my brother, together. I seen ‘em.”

“So, your brother dies in a floodin’ river and your wife’s dead by you hangin’ her. You feel better ‘bout things now, William? You set things right?”

I began to walk slowly toward him. “William, I want you to go up that tree and cut her down and bury her.”

He stood up and turned toward me. He had a pistol in his belt. “She couldn’t bear no children, Zeb. What good’s a woman that cain’t bear no children?”

I walked closer. “William, I want you to climb that tree and cut her down I tell ya, then you’re gonna bury her decent.”

“I will not! She don’t deserve to be buried.”

“You know Son, there’s a lotta faithless folks in this world dead and alive and she may’ve been one of ‘em . . . but she don’t deserve to be left hangin’ for the crows to get at.”

Someone brought a lantern and a shovel. Someone else picked up the rabbits and took them back to camp.

“Who’re you to tell me what to do? If it weren’t for you, we’d be half way farther up the trail and not walkin’ and my brother’d be alive.”

He took a step toward me.

“If it weren’t for you and your brother, we’d have all our wagons. I told you that ford was no good, but you crossed anyway. ‘Cause a you, those other folks followed and were swept away. God only knows how you and her stayed alive and now she’s dead. And, come hell or high water I got to get the rest of these good folks to safe quarters at Fort Union. We seen the high water and I expect we’re comin’ into hell soon enough. Now I will stand here and argue no more. It’s getting colder and I expect to be eatin’ rabbit stew soon. Cut your wife down, William. You’re buryin’ her decent.”

I stood near four strides away with my rifle raised. What folks left listening stood behind me.

He squared up, laid a hand on his pistol and said, “I ain’t cuttin’ no good rope.”

“You were gonna leave the rope swingin’ with her. Now I don’t give a goddamn how you get her down but you’re goin’ to, else we’re buryin’ two folks tonight.”

Stars were shining by then and standing there in the cold we could hear her petticoats rustling above our heads. He turned a little and looked up.

*****

William buried her by moonlight. We could hear him sobbing, digging and scraping. Every once in a while, he would just let out a scream, then nothing.

In the morning, a couple of the men went looking for him, but he was gone.

To Be Continued . . .